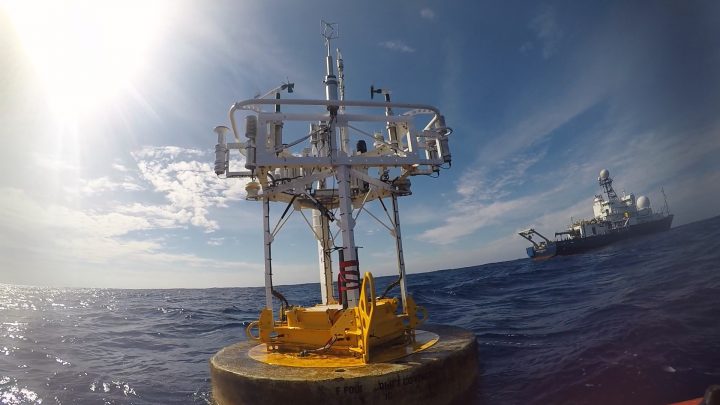

WHOI Mooring Buoy (credit Ray Graham).

One of the reasons our work requires a large research vessel is that we are dealing with large arrays of sensors moored in the deep ocean. That requires big buoys, lots of rope and wire, lots of floatation, and big anchors with very strong and steady human guidance.

Time series collected from moorings are among the most valuable data sets collected in oceanography. Anchoring sensors at one location and precisely placing them at pre-determined depths provides a view of the ocean that cannot be supplied by any other means.

SPURS-2 deployed three moorings in late summer of 2016 and recover the equipment now, in November 2017. Our “central mooring” from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is heavily instrumented with temperature, salinity, and velocity sensors (See Prior Blogs: Mooring Deployments and Mooring Deployment). Two additional moorings from NOAA PMEL (See Prior Blog: NOAA Contributions to SPURS) are instrumented with “Prawlers” (See prior blog: Prawlers, Engineers, and the Future of Oceanography at Sea) – a single sensor package that crawls up and down the mooring wire profiling the water column. In addition to ocean measurements, these moorings provide a year long record of the surface meteorological conditions.

Silky Shark on the line at WHOI mooring.

One of the interesting thing about these moorings, that you seldom hear about, is the “buoy ride.” Several times during this voyage we have put men on the mooring buoy to complete assignments such as replace batteries, change out meteorological gear, and finally to remove all the meteorological equipment in preparation for recovery of the entire mooring. Ben Pietro and Ray Graham described the experience quite vividly – of clambering aboard the buoy from Revelle’s small boat and attempting to stay safe on a rocking, rolling, heaving, slippery, guano-encrusted, shark-surrounded, pillar of modern oceanography.

In the approach via small boat, we are told, one is impressed immediately by the number and variety of fish swimming around the buoy. There are also the menacing, shadowy figures of sharks among the fast-swimming tuna and mahimahi. That gives the short leap from the boat to the buoy the feeling of a do-or-die effort!

Once aboard the buoy the footing is slippery with seawater and guano, so the discipline of a rock climber is required. It may be only a short way down, but who wants to splash around with hungry sharks? One only has to recall the fishing, of days recently past, where on one cast all that was brought aboard was the lure and the head of the tuna; the sharks having won an easy and quick dinner. Best to hold on tight. Ben said his knees were sore from clamping down hard on the buoy while using both hands to get the meteorological gear free and stowed.

Serious profession this!

Ray and Ben riding the WHOI Buoy!

One of the fascinating projects to watch during the mooring recovery is the dismantling of the “hardhats” – the mass of floatation at the bottom of the mooring above the anchor that brings the bottom end to the surface. As deployed, it is a tall tidy assembly of glass balls in their protective hardhats, in bunches of four, connected with chains. As recovered (see photo), it is a confusing puzzle of twisted chain and shackles in an untidy pile. Amazingly, it took a dozen people only twenty minutes to untangle the puzzle and stow the hardhats four by four back in their shipping box (AKA, the snake pit). Honestly, it was an amazing operation to watch!

The Puzzle of Untangling the Hardhats.

While ocean moorings are often described as autonomous observing platforms, the human ingenuity required to deploy and recover them demands a steady human with a tight grip.

Tags: oceanography, salinity, SPURS, SPURS2